Watch This Space

Originally presented as the keynote lecture at STRP Festival March 2015.

Watch This

Space

Text Francesca

Gavin

This is an

examination about our relationship to screens. How that association is changing

our daily experience, our ways of thinking, our ways of looking. Lets start

small – with the phone. It is the most intimate example of our relationship to

technology. The screen-object we carry with us everyday.

If you search

“looking at phone” what comes up is a YouTube clip of people staring at their

phones. It is described as “an epidemic of texting while walking” and

positioned as something seriously dangerous. Illustrated by funny amateur phone

footage, this humorous news excerpt is a perfect example of our relationship

with our phones. How we fall into our focus on the screen – forgetting the

physical space around us. Forgetting our own physicality. I love the

phrase “inattention blindness”. But in fact, it is the opposite. The people

featured are consumed with attention – they are just looking down at the object

in their hands not at their ‘real’ surroundings.

Where is the screen?

Where is the

screen in contemporary life? We wake up and check our screens for messages. If

we travel to work on public transport, more than half of us are on our phones.

We stare at screens for work, communication, play and diversion throughout the

day. Travel home, and watch a screen again for entertainment. Sometimes with a

second screen on our lap. Then we go to sleep with our screens next to our

beds. We experience screens in advertising – moving alongside us on the

escalator, blown up in public space. At music gigs or exhibitions or cultural

experiences, everyone is watching things through their screens, capturing the

moment in some form. Amateur mobile screen footage is now normal on the news. As James

Bridle in his essay ‘The New Aesthetic and Its Politics” writes, “protest,

repression, revolt and schism are framed not through the lens of critique, but

the lens of iPhones and iPads held aloft.”

In recent

years, there has been a wave of literature deconstructing our relationship to

technology – often criticising it even from within. Jaron Lanier, an American

computer scientist and pioneer of virtual reality, in his book ‘You Are Not A

Gadget’ from 2010 criticised the limitations of the structure of programming

and how it restricts human expression and communication. Devices, he notes, are

“inert tools and are only useful because people have the magical ability to

communicate meaning through them… The most important thing to ask about any

technology is how it changes people.”

For me the

most influential text to sum up our experience with technology and what it

means to exist now is Jonathan Crary’s ‘24/7’ that appeared last year.

Subtitled ‘Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep’, the book is deeply critical

of the political and commercial interests that oversee our relationship to

technology. If you’re checking your emails or feeds in the middle of the night

on the tablet next to your pillow, this book will make you feel very

uncomfortable. In particular much of the focus of the book is on the speed of

consumption – the current accelerated formats of image and information

absorption. Nothing is ever really off – just resting, waiting to be activated

at a single gesture, touch or glance. Here the screen becomes a device that is limiting

not increasing our activity. To quote Crary, “Devices are introduced (and no

doubt labelled as revolutionary), they will simply be facilitating the

perpetuation of the same banal exercise of non-stop consumption, social

isolation, and political powerlessness.”

Crary points

out how the myths of open source egalitarianism and the empowerment of

technology have been cultivated. “The idea of technological change as

quasi-autonomous, driven by some process of auto-poesis or self-organisation,

allows many aspects of contemporary social reality to be accepted as necessary,

unalterable circumstances, akin to facts of nature. In the false placement of

today’s most visible products and devices within an explanatory lineage that

include the wheel, the pointed arch, movable type and so forth, there is a

concealment of the most important techniques invented in the last 150 years:

the various systems for the management and control of human beings.” To

paraphrase, we voluntarily kettle ourselves in cyberspace.

The screen as interface

My aim here is

not to join the choir of criticism. Though my feelings are ambivalent – a

midpoint between horror and fascination, admiration and addiction. Rather than

the wider discussion around technology, I want to focus on the interface – the

screen itself. Many theorists have focused on the content of the screen – the

ideas around the network and the effect of technology on our psychology,

actions and thinking. Yet there is very little discussion about the black

void-like rectangles we stare into so much. To begin with, what is a screen?

When I first

started thinking about this topic it was such an easy thing. It was something

that grew directly out of the construction and composition of painting –

referencing the dimensions and constructions of the canvas. The modern screen

was an extension of the cinema screen and the television, which became the

monitor, the laptop screen, the phone screen and the flatscreen. Yet, as the

academic and writer Peter Lunenfeld pointed out to me, my conception was

perhaps limited. “The newest screens really are sort of only pseudo screens.”

The screen today is no longer necessarily a black rectangle or square. It is

also an a oculus rift headset or a projected surface with moving imagery like

the blank tunnels on the London tube system which are transformed into screens

between trains. The screen has moved beyond the confines of the screen.

Scale is

something Peter also discussed with me - the emergence of the ‘phablet’. A

phone with a bigger screen space to watch things on. In the 21st

century we are seeing a move away from mid ‘human’ size towards the tiny or the

supersized. The same applies to narrative itself. “The classic Aristotelian

dramatic unity of the 90 to the 120 minute theatrical presentation, which moves

from Greek theatre into medieval passion plays, into narrative length films -

that just disappears in favour of the Vine at six seconds and Game of Thrones

at 28 hours.” There is a strong connection between how and what we watch and

the changes in our devices.

The New Intimacy

I think one of

the most interesting changes in our relationship to the screen is a new sense

of intimacy. Screens live in our pockets, our bags. We often touch them or

check them for reassurance. Sometimes numerous times per hour. The content of

the screen is life. As Baudrillard the postmodern French sociologist and

philosopher wrote in his essay ‘Screened Out’ in 1996: “Distance is abolished….

between stage and auditorium, between subject and object, between the real and

its double.” He goes on, “There is no separation any longer, no empty space, no

absence: you enter the screen and the visual image unhindered… The video image

– and the computer screen – induce a kind of immersion, a sort of umbilical

relation, of ‘tactile’ interaction as McLuhan in his day said of television…”

Here our addiction and relationship to the screen is fuelled partly by a desire

for self-immolation. As Baudrillard states, “from the desire to disappear, and

the possibility of dissolving oneself into a phantom of conviviality.”

Screens have a

bad reputation. They are blamed for eye ache, sleep damage, rewired brains, and

social isolation. A recent Norwegian study observed teens slept less when they

used computer screens more. The artificial light activated wakefulness and

suppressed melatonin. Charles Arthur, in his 2008 article in The Guardian ‘It's

the screens, not the internet, that are making us stupid’ wrote, “Low resolution

monitors (including all computer screens until now) have poor readability:

people read about 25% slower from computer screens that from printed paper.” A

study from Manchester University found reading on paper 10-30% faster than on

screens. (Interestingly the screen is always being positioned in contrast to

the book page – again a throw back to the work of Marshall McLuhan.)

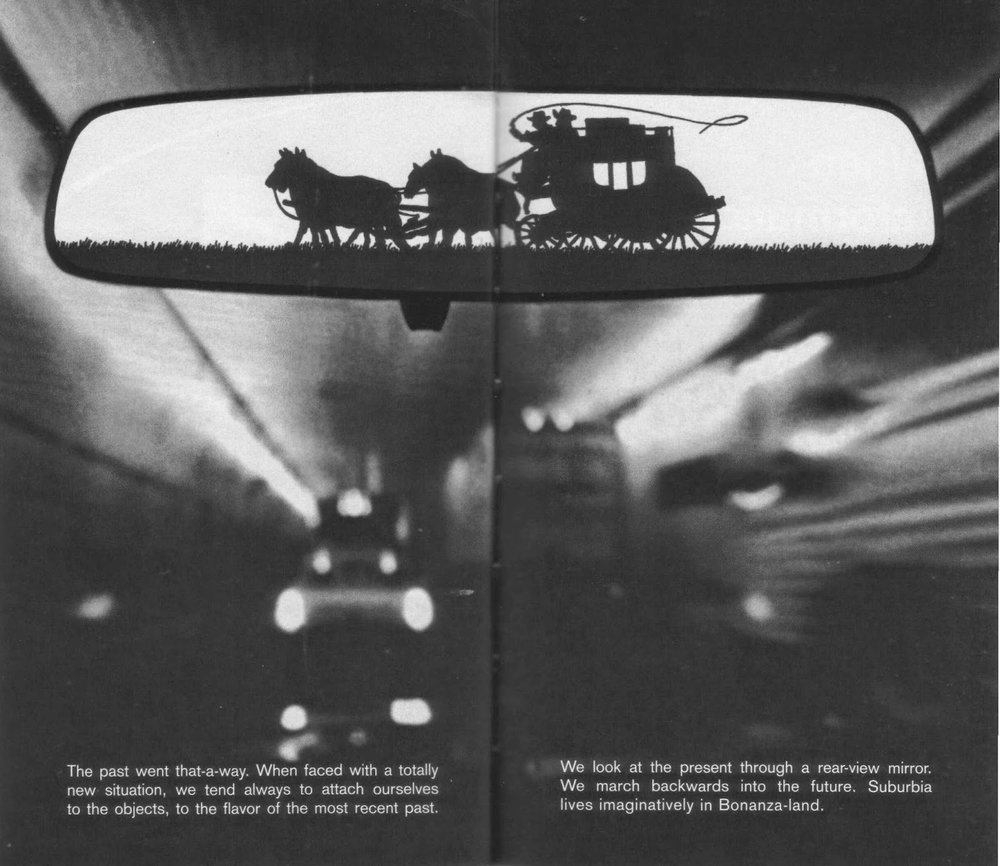

In McLuhan’s

‘The Medium is the Massage’ the focus was the television, yet his ideas could

easily be applied to the modern screen. He writes, “In television there occurs

an extension of the sense of active, exploratory touch which involves all the

senses simultaneously, rather than that of sight phenomena, the visual is only

one component in a complex interplay… Television demands participation... It

will not work as background. It engages you. Perhaps this is why so many people

feel their identity has been threatened.” Its amusing to think anyone would

feel this way about TV after so much more invasive technology has been developed.

The

screen has increasingly become a space for human psychological expression or

dissolution or distrust. Andre Nusselder’s in ‘Interface Fantasy:

A Lacanian Cyborg Onotology’ argues that the computer functions in cyberspace

as a psychological space – as the screen of fantasy. At one point she mentions

the work of MIT professor Jozeph Weizenbaum, who wrote the first computer

psychotherapy program ELIZA in 1966 – which Lacan was fascinated by. She explains, “Lacan

acknowledged that ELIZA appears to produce some sort of transference relation.

People find something (of themselves) in the machine; they unconsciously

transfer (fantasmically) the object of their desire onto it. Computers may

appear as fellow “humans”: you can talk to them, they can ask you questions,

you can play and cooperate with them.” We see our screens as sentient.

Psychologist

Sherry Turkle has been strongly critical of the changing emotional fallout from

technological developments. In ‘Life on Screen’ (1995) she writes, “We have

learned to take things at interface value. We are moving towards a culture of

simulation in which people are increasingly uncomfortable with substituting

representations of reality for the real”. More recently in her 2012 Ted Talk

‘Connected, but alone?’ she laments the opportunity for self-editing and

distance that technology allows us. “Texting, emailing, posting lets us

present the self as we want it to be. We get to retouch. Human relationships

are messy. We clean them up with technology. We sacrifice conversation for

connection.” She notes that the phone presents the fantasy that we are never

alone, will always be heard. “Being alone feels like a problem that needs to be

solved. I share therefore I am.”

Future Fantasies

The future

looks even crazier. The TV series ‘Wild Palms’ is a great metaphor for the

possibilities of what the screen can be. This mini series was released in 1990

– following the avant-garde approach of Twin Peaks. It was based on a comic

strip by Bruce Wagner. It was partly created and produced by Oliver Stone with

episodes directed by Kathryn Bigelow among others. The series focused on a

future Hollywood in a fictionalised 2007 where an underground movement, the

Friends, were in resistance to the right wing Fathers who owned the media and

had political and religious control. The way the populace were manipulated and

controlled was through a virtual reality holographic technique ‘Mimecom’. The

protagonist’s son is set to star in a Channel 3 series “Church Windows” using

this new media, which would project a holographic character into your domestic

space. Here the screen literally broke out of the fourth wall and touched you.

This was an exploration of the possibilities of virtual reality (sometimes

exaggerated by an addictive drug mimezine).

Steven

Spielberg’s ‘Minority Report’ provides another metaphor of the transformed

screen – in the context of marketing, advertising and consumerism. You could

literally feel capitalists get turned on the minute that film was released.

Both of these examples highlight something central to what a lot of artists and

writers are highlighting – the ownership and possible exploitation of

technology. (Something Lunenfeld explores very well in his book ‘The Secret War

Between Uploading and Downloading’).

There are

rumours of Facebook’s messenger app recording people’s conversations and

ruffled feathers over Samsung's amended Terms and Conditions warning users of

their Smart TVs that [records?] conversations within earshot of their products.

The screen is watching us as much as we are watching the screen. Television

today is often a two-screen interaction – with phones and tablet interaction

encouraged to revive traditional passive media. Sony have just patented

methods, systems, and computer programs for converting television commercials

into interactive network video games. In one method, a broadcast or streamed

commercial is accompanied by an interactive segment. A media player would

present users with an enhanced and interactive mini-game commercial that could

be played with other ‘viewers’. It could be inserted within the television

program, overlaid on frames or last the duration of a commercial spot.

Interactive adverts already exist on services like Hulu.

Ageing Technology

Getting back

to the present, it is also important to define what the modern screen’s

appearance is. It has its own texture, colour and illumination. Many artists

that are making work today reflect this – like Rafaël Rozendaal, who will be

talking later today, the digital animations of Daniel Swan, the projections and

print work by Travess Smalley. The way images disintegrate on the modern screen

is also very important. Laura Marks writes in ‘Touch: Sensuous theory and

multisensory media’: “The noise of a failed Internet connection Soundbite? is a

declaration of electronic independence. It grabs us back from the virtual space

and reminds us of the physicality of our machines.” She emphasises that digital

media are in fact analogue. They are unpredictable, make errors, breakdown,

connections cut out – these are all things that remind us of technology’s

physicality rather than its transcendence. Failure is inbuilt into technology

design. As Marks puts it “technologies age and die just as people do.” It is

just manufacturers and techno evangelists with vested interest that make us

want to dream it is superhuman.

Esther Leslie

in her Slade Contemporary Lecture of 2010 questioned “Is there a liquid crystalaesthetic?” For Leslie, HD screens are the new contemporary media in

themselves. The ability of LCD and plasma screens to be flicker free, still at

any moment and negate the time progression of narrative is influencing creative

content. Here art’s progress is bound up with the imitation of nature – depth,

perspective etc. The definition of mimesis. Today’s photorealistic 3D animation

attempts to do the same thing – to make fiction invisible. Yet at the same time

digitization is a simulation. A computer transforms an image into pixels, code,

a language – the result is a version of something.

We can

conclude that the screen is complex. It is becoming the focus for all kinds of

issues of modern life. Physical, psychological, cultural, political. We have

never been more obsessed with looking at the moving or still image in screen

space. Nathan Jeurgenson notes in ‘The IRL Fetish’ “the plain fact that our

lived reality is the result of the constant interpenetration of the online and

offline.”

Between the Passive and the Active

So how are

artists addressing this relationship? I think this can be positioned between

the idea of the passive and active screen. The passive screen is one observed,

a screen as object. In its most simple form, this is a screen we watch. CamilleHenrot ‘Grosse Fatigue’ (2013) is a beautiful example of a film, which

documents our computer screen relationship. The piece examines the way we look

and accumulate information. There is a strong sense of rhythm and editing in

the work, which was developed during a residency fellowship at the Smithsonian.

She discussed

the project with me in 2013. “I was doing a lot of Internet research on the

Smithsonian database. I often had a lot of windows open on my desktop. When you

look at a cluster of windows on a desktop and try to find reason, it results in

a kind of primitive thinking – a sort of ultra rationality. You see the images

together and then your mind makes these connections, not because there is a

connection but because your brain needs to resolve the images.”

Here the

screen becomes the subject of work itself. Shown as a projection, nonetheless

our engagement is one of observer watching the film from the point of a

relatively passive audience. Another contemporary example of this passive,

observant screen relationship is Dis’ #Artselfie project, which was recently

released as a book.

Part art

project, part viral meme, the artselfie revealed the audience’s desire to

capture themselves alongside the artwork, even inside the artwork. The subjects

become temporary collectors who are able to have their experience intertwined

with a digital ownership of the work in some form – even if only within the

screenscape. The results feel like a prosaic take on performance documentation.

In this way the art object becomes something communal, sharable and conceptual

rather than physical.

Samara Scott

is an artist better known for her work in 2D space – sculptures, paintings and

installation pieces. However, she created a fascinating web project for Legion

TV that I think is of note as an example of an artist drawing on ideas of the

passive screen interaction. Scott is interested in how the screen perverts gaze

– “shifts and melts and inverts natural legibility”. Her work was an attempt to

make a narrative film but this emerged as a diary of snapchats and scenes she

had casually collected placed together on the screen, which popped up over

whatever was on the viewer’s desktop. Playing with the logic of collage, this

moving image was largely footage of textures, soft things, hard things, woven

objects. “Textual encounters” as she puts it. The result was a very visceral

experience to watch – a digital creation of sensation. She is currently making

a body of work photographing and filming sanitising hand gel on an iPad.

The Screen as Object

The next stage

of the passive screen is one where the screen is embedded in the work – often

within the sculptural or painting field. Ken Okiishi does this by making the

screen into a canvas for paintings. Nate Boyce does this by making sculptural

plinth part of a work holding a screen. The work of British based artist Adham Faramawy is a great example, placing screens within complex sculptural objects. Based in the UK, originally from Egypt and

is a graduate of the RA schools. He was originally influenced by the arrival of

flat screen TVs and how they were replacing cathode ray monitors and the way

this changed how we receive and perceive an image.

His use of the embedded screen emerged after

he began working with animators to produce sculptural computer programs and

later particle animation. “I started to get familiar with the logics and the

languages of the interfaces to the programs producing these moving images.

They're inherited from analogue, physical traditions like film editing, clay

modelling and masonry, but unlike the given conditions of these traditions,

with computer modelling you can't make assumptions, you have to assign physical

conditions and physics to an object.” contained within highly textured cases

and plinth structures. Often the screen is upturned in his work. He explains,

“Shifting the angles at which a viewer receives an image was, for me, intended

to point at the physicality of the image, thinking about the substrata carrying

that image as a sculptural body, a form within a composition.”

Another

passive example of screen use is deconstructed and taken apart but still

functions in some way as a screen. One example would be the work of Yuri Pattison, an artist who is currently in residence at the Chisenhale Gallery and

was part of the collective Lucky PDF. He has used digital signage monitors,

which present self shot iPhone footage – commenting on our consumption of

screen based information. His current interest is in e-ink panels. Pattison often

takes apart screens and displays their inner workings, revealing the mechanisms

of display. As a result, we can see a small number of manufacturers are making

these parts – Samsung panels are being used by numerous brands for example. He

removes the façade of slick design and marketing. “The stripping of the screens

cosmetic body and branding also highlights the mechanisms that support the

display of the image – these mechanisms are normally invisible, deliberately

hidden by the manufacturer to present a seamless experience.” Pattison notes.

“We view screens as a window on to something, so in the way we don't think of

the glass in the window we don't think of the processes behind the

representation on the screen. There are numerous layers we don't perceive, or

barely perceive, in the act of viewing something on a screen.”

Berlin-based

artist Simon Denny who is representing New Zealand in the next Venice Biennale

is very interested in a deconstructed screen. His work has examined TV hacking,

the thinning of monitor, how we receive information, the design, packaging and

structure of the companies behind the consumption of technology, and

conferences that promote and position devices in society. Here the screen is

printed on panels. Analogue materials replicate the structure and format of the

screen. The screen is ripped apart, reimagined and revealed.

Another way

the passive screen is explored in artworks is when it is translated into

something outside of the screen – the screen space in real space so to speak.

Dutch artist Constant Dullaart does this well. “The screen is our contemporary

landscape. We spend more time daydreaming and staring at screens then we look

out of windows. The screen is a personal experience more and more, which brand,

design or lifestyle you subscribe to. This fetishisation of the private

experience seems to be a response to knowing most networked screen based

communication is not private at all,” he points out. “How private can a screen

get, can it get more private then the Oculus Rift, Microsoft Hololens, or

Google Glass? If we have these private views, are we leaving our shared

experiences to be mediated by commercial companies?”

The active screen

The next level

artists are engaged with the screen as what I’m going to call the active

screen. This is where artists are exploring ideas around interaction and space.

I curated a show called ‘Responsive Eyes’ a couple of years ago that I want to

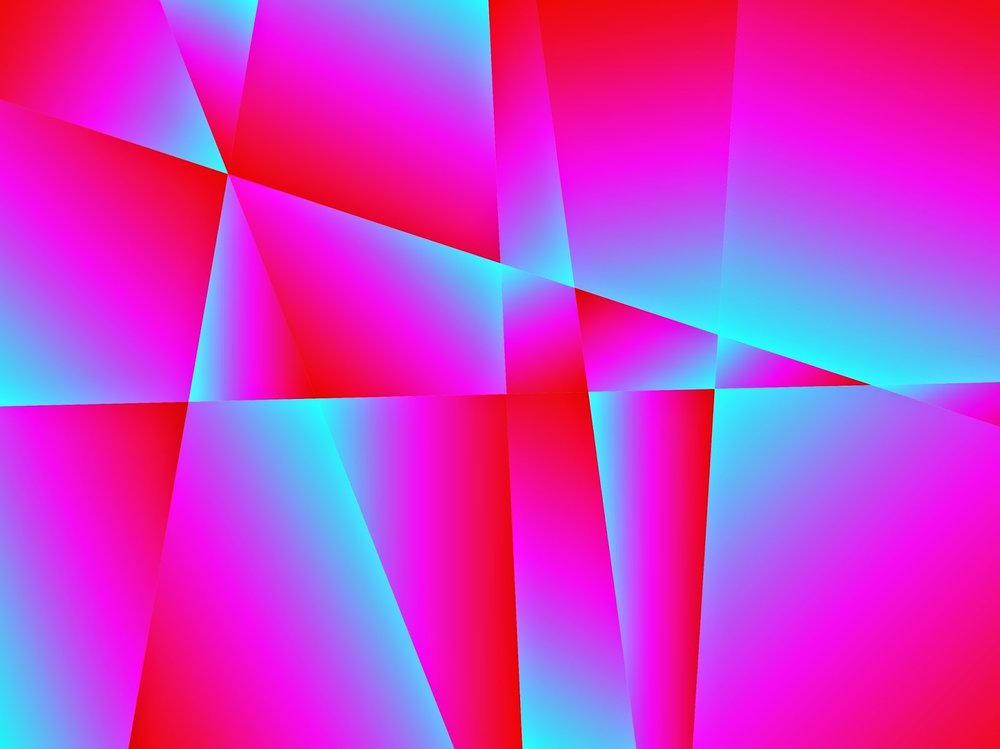

bring up at this point. It was inspired by documentation of the opening of ‘The

Responsive Eye’ an exhibition held at MOMA in New York in 1965. It brought

together artworks by so-called ‘Op’ and minimalist artists such as Bridget

Riley, Josef Albers and Viktor Vasarely. The curator William Seitz described

the show an “exhibition that would indicate an activity, not a kind of art”. He

argued in the exhibition’s catalogue this was “non-objective perceptual art”,

art that “exists primarily for its impact on reception rather than for

conceptual examination… Ideological focus has moved from the outside world,

passed through the work as object, and entered the incompletely explored region

area between the cornea and the brain.”

The reason I

wanted to highlight this moment in art is because I think our interaction with

the screen has decades of legacy of technological advancements that have played

with human perception and physicality. I want to connect these ‘retinal’ works

with gifs, digital paintings and 3D animation. How we relate and view the

constant influx of movement, imagery, sound and informational content in modern

screen life.

The exploration

of screen interaction can be lo fi. Aram Bartholl’s show which closed earlier

this month at Baby Castles in New York questioned the screen perspective. “Most

of our reality today is taking place in that phone rectangle. The screen

constantly moved closer to our eyes over the past decades (from cinema to

phones). The screen will be attached to our eyes soon (glasses or lenses).”

Playing on the exchange and selling of imagery though the screen, Bartholl’s

exhibition was very much made for interaction and dispersion through social

media. He created giant photo picture cut outs so people could pose as if

within the phone screenspace for Instagram, Twitter or Facebook. The main aim

was to get visitors to interact with each other.

Selfie sticks,

head mounted cameras like GoPro or Google Glass played with the idea of the POV

image (what is this?). He created head mounted phones during a workshop at the

Atlantic Center of the Arts, experimenting with filming POV techniques. “In the

end it appeared to me that the picture of someone wearing his/her phone on the

forehead obviously filming is even more interesting than the actual clip shot

with that head mounted phone.” He explains, “The whole thing is a bit cyborg

but in a silly, lite [light?] way.”

The active or

living screen can be seen in the work of Antoine Catala. In his video

projection works and sculptural installations the screen appears to literally

come to life. He uses membranes that appear to be breathing, moving in a techno

organic way. He has streamed television into fluid blobs shapes – ‘alive’ in

some form. He uses display technology and reflection to create screen-like

space. Many of these pieces are a step beyond a mere passive screen as it is

one alive, in flux – closer to the conceptual approach of someone like Bruce

Nauman and his real time video experiments. Our engagement may still be as

observers but the screen itself comes to life in some way.

The Human Touch

The next level

of active screen is one that is activated by human touch or a click – such as

in the online installation pieces by Brenna Murphy or the websites by Rafaël

Rozendaal. Murphy makes immersive installation pieces in real space, often with

sound elements and performance, but her interactive pieces are largely based

online. The intimacy of the screen relationship is key. “I make art that is

meant to be viewed on the Internet by people privately browsing from their own

device. I think this is an intimate and powerful way of transmitting and

experiencing media.” Here viewers click on audio files so they overlap with

rhythmic gifs, video montage and scrolling images she makes from her own video

footage. The results are very psychedelic. Clicking on images takes us through

a maze of digital collage imagery. The aim of her web ‘Labyrinths’ is to make us conscious

of the role of the screen.

Her work is so

successful because it relates to how we are used to using our screens for input

and interaction. The simple click and arrow (or in some examples touch). Other

artists also create active screen works that replicate the interactive pathways

and experience of exploring the Internet, such as the online questionnaires and

page-to-page pathways of Cecile B Evans’ online project for Serpentine Gallery

AGNES. A spambot that generates experiences beyond the virtual, and created a

sense of connection and emotion query. Here the screen touches on those

sensations of Lacanian transference

The active

screen relationship is very clear in artworks that draw on gaming –

increasingly a source of inspiration for a generation of artists including

Lawrence Lek, Tabor Robak and the Dutch artist Rosa Menkman of whom we will

also see work in the Vertical Cinema program tonight. Games give the illusion

of interactive but in fact the audience is still largely controlled by the

artist, the developer, the structure of the screen – something that

metaphorical reflects our relationship to technology and screens as a whole.

Devices that, for the majority of users, force us into a passive position.

There are also

structural and aesthetic aspects of screen game interactivity that emerge. Jon

Rafman and Rosa Aiello’s online film work “Beyond Carthage” was conceived of

spaces from “Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception” and “Second Life” to look at ideas

around history and self through largely architectural spaces. As Aiello notes,

“The decay and historical movement of a digital object occurs laterally,

through pixellation and a loss of image quality, rather than by rusting or

crumbling or scars.”

Ben Washington

is an incredible British artist using the interactive screen in his

exhibitions. He creates sculptural installations in galleries and then

recreates these spaces, though often with strange failure and pathways, digital

as an interactive game he places within the exhibition space. The viewer

(standing behind the controls of an arcade machine) will, for example, find

themselves in a virtual version of the exact same physical gallery space in

which they are standing.

The result is

an experience that contrasts seeing the real and the virtual version of

something at the same time. They both become fused and influenced by each

other. Washington explained to me, “the interest between screen space and real

space arises at the point at which they converge and diverge. The focus in my

work has been on these uncanny moments.”

The

interactive nature of the screen is of particular note to Washington from a

more social perspective. He points out, “How much we are going to let the

screen encroach into real space and into our social norms? Already it is

evident that socially it is now almost totally acceptable to wander around with

your face in a smart phone. And you would expect newer technologies such as

Google glass, and interactions such as augmented reality, but interestingly it

feels that both these developments have stalled. I’m as interested as much by

that which we decide to discard along the way as that which we finally decide

to assimilate with.”

Washington was

particularly excited by development kits being produced for Oculus Rift and the

other contenders in the Virtual Reality market – Sony's ‘Morpheus’, ‘Steam VR’

and the ‘Sulon Cortex’. William Gibson’s version of cyberspace made flesh.

Director David Mullett, who is currently working on a VR project and has been

writing on the subject, describes the attraction of the VR screen. “VR has a

frame in the sense that it is a screen tied to your face – but with a software

coding sleight of hand and optics advancements alongside the accelerometers and

gyroscopes built into smart phones, it appears as if there is no frame

whatsoever. And our relationship to screens is so addictive and obsessive

that we need to ramp up our stimulation to tug the emotions or get that

dopamine hit we are so hungry for.”

Artists are

beginning to experiment with VR itself in a more conceptual way rather than

gaming context. The Sundance film festival had a whole VR exhibition project.

Oscar Raby’s ‘Assent’ documented the artist’ cathartic exploration of his

father’s traumatic memory of a mass execution in Chile in the seventies. Part

interactive, part cinematic a physical and poetic journey into trauma. A hybrid

between first person gaming and the protagonist in a film narrative.

Perspective’ by Morris May and Rose Troche reveals an extremity of first-person

filmmaking where the audience is put in the shoes of a teenage girl being date

raped at a house party, then in the shoes of the guy doing to raping.

Max Rheiner’s

‘Birdly’ is a flying-simulation installation where your entire body is used to

fly like in a dream. As Mullet notes, “With VR immersion, your unconscious

brain actually thinks that it is doing these things, indicating that the

technology will rewire our brains in critical ways with extent of use and

intensity of experience.” He imagines flipping through immersive channels like

TV surfing.

As the

boundaries of the screen transform the future is looking pretty crazy – though

I admit the excitement and fantasy of tech literature over the past twenty or

so years always sees wild changes on the near horizon. Writer, curator and artist

Sam Hart sees the post screen future for art as something more to do with the

structure of the internet itself. In fact a new decentralised Internet. Artwork

coming out of the blockchain space.

As Hart

explains, “the blockchain is nothing more than a publicly visible, distributed

database whose entries are immutable once instantiated. The “blocks,” or

records, comprising the database are uniquely addressed and have a

cryptographic key which entails ownership.” Hart suggests this space could

become a novel medium for digital art by encoding line and colour values,

sequences and relationships. The yet to be launched platform for decentralized

applications Ethereum (www.ethereum.org), for example, embeds an

entire programming language for design. As Hart explains, “I think it

represents a significant progression in digital artistry: a uniquely relational

medium that circulates through body and network by way of the screen.” The

results are unknowable at this time but these new languages point to new screen

based structures to create work within and upon. As Lanier points out, the structure

of programming has a huge influence on the results we experience. Rethink our

entire approach to that and you have a different future in formation.

So where does

this leave us and our little black screens? Sam Hart sees the screen as “a

hopeful object, representing possibility better than most anything.” Despite

the anxiety around them, they are the site of a lot of creativity. It is

impossible to be comprehensive in the many ways artists are using the screen in

their work – what is so interesting is how varied approaches are. Interactive,

passive, three dimensional, flattened, virtual, literal – the screen has a lot

more conceptual depth than a void. In fact the void-like nature of the screen

can be seen as what makes it so exciting. It is waiting to be filled with

imagery, information

and ideas.

(c) Francesca Gavin 2015